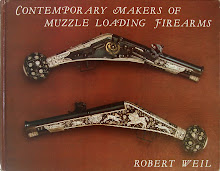

The work

of Mitch Yates caught my eye when I started to see his engraved representations

of animals and designs on silver that were unmistakably true to the style and

feel of the 18th Century and earlier. He has also created some wonderful

flintlock firearms that show the restrained yet detailed hand of an artist

dedicated to precision and form. So, I asked him a few questions about

himself and his work:

How did you get started down this path?

As far

back as I can remember I’ve had an interest in history and hand-work. At

a very young age I accompanied my father on a trip to Grey Owl Trading (A

company that dealt in Native American Craft Supplies) and he purchased a loom

for me to try my hand at beadwork. At 14 I saw the movie Jeramiah Johnson

and received a Thompson Center Hawken as a Christmas present which was my entry

in muzzleloading. At 17 I entered the construction trades, and after

working on an historical restoration of the last standing blacksmith shop in my

hometown, I took up blacksmithing. I gradually moved from construction

work to opening my own custom cabinet/furniture shop catering to the wealthy of

“The Hamptons” (an affluent seaside community located in Long Island, New

York). A chance to go elk hunting in Colorado prompted me to combine wood and

metal working and build my first gun. Full-time gunmaking and

silversmithing followed.

Did anyone in particular influence or teach you?

When I

was 19 I stared working for a man named Al Kahkonen. He was a bit of a renaissance man who was skilled in many different kinds of

hand-work and had a deep interest in the 18th Century. Al not only enjoyed making items from the 18th Century...his passion was using proper 18th Century tools and methods. His attitude was that with a little

God given talent in your hands, a thirst for knowledge and lots of

perseverance, there isn’t anything you can’t make or accomplish. That

attitude has served me well in life.

I studied

Gun Building at the NMLRA Gunsmithing School in Lexington Kentucky. While

there I studied under the likes of Wallace Gusler, Gary Brumfield, Jim Chambers

and Hershal House, probably one of the best experiences in my life.

Lately Mark Thomas has been a huge help as I’ve started to work more and

more with silver. Mark is another of those craftsmen who work in many different

mediums and materials and does incredible work. These are just a few,

I’ve left many out as there are just too many to mention here. One of the

great things about this community that we are a part of is a willingness to

help and share knowledge. I can do what I can because someone took the

time to share their knowledge with me. For this I am grateful.

When did you first start engraving?

I first

started engraving about ten years ago. After fumbling around on my own

for a while I took an engraving class with Wallace Gusler. It helped me

improve some but I never really felt good about what I was doing. A

couple of years ago at my lovely wife’s urging I stared making trade

silver. I viewed it as a way to improve and get more comfortable with

engraving. It’s worked out well, not only allowing me to practice weekly

but it has become a big part of my business. I’m finally starting to see my engraving

improve to a level that I’m happy with.

Do you teach or instruct at all?

I try to

share what I know to anyone who is interested. I’ve taught some

woodworking and blacksmithing in the past, and I’ve been doing some seminars at

Dixon’s Gunmaker Fair and will continue to do so. I know what I know

because someone shared with me, so I feel an obligation to pass on what I know.

What is your process when you set out to make a piece?

Most of

my work is heavily based on original 18th century examples. My basic philosophy when making something

is that when it’s done it should look like I trained in the 18th Century shop where it was originally made. Even if it’s not

an exact copy, my “master” could be identified by studying my work. To

that end I spend a lot of time studying tool marks and how carving/engraving

was cut. This also means that 18th Century tools and techniques are used whenever possible. I

begin by studying/researching the details of the original piece, make whatever

patterns and tools that are necessary, and then I make the piece.

What is your favorite material to work with?

I would

say my favorite is whatever I’m working on at the moment. I have found

the key to keep from getting bored in my work is to kind of jump from one thing

to another, trying to be make each one more difficult than the last. I

maintain photos/files of things that I want to try to make that will challenge

my skills and interest my clients.

When you create a gun, do you make any of the components from

scratch? Does that change the creative process in any way?

For the

most part, with the exception of the lock and barrel, I make as many of the

parts as I can or the customers budget will allow. I regularly make my

own patchboxes, ramrod pipes, sideplates, inlays, and forge my own iron

mounts. With the exception of forging a barrel( which is on my bucket

list) I’ve made all the other parts of a rifle at one time or another.

Making your own parts greatly expands the creative process as it broadens your artistic

possibilities is the best way to avoid the “cookie cutter” look in your work.

The borders, overall designs and other elements of your engraving

work in particular shows you have an instinct and innate skill for composition

and layout. Does much of the original work you've seen and studied show

this same level of composition?

Almost

all the “art” on my work is either taken directly from original work or is

inspired by it. In the period, work showed wide variations in

complexity. European work was of a much higher quality than American work

for the most part. The long established guild system in Europe meant

artists were very well trained and their skills were honed from a young age.

Their work showed a much higher level of composition and execution. I try and

match the level of my work to the original piece I am trying to recreate. I

often joke that one reason my engraving looks right for most American 18th

century work is that I’m not a great engraver, and neither were the original workers

that I mimic. There were certainly master engravers in the period, but

most of the American work (as opposed to European) that interests or inspires

me would be considered “folk art”. I find that sometimes the little

imperfections are what’s interesting about a piece. It’s one of the

reasons I stick with a hand hammer and graver rather than a powered

graver. My personal goal is to be as good as I can be with a hammer and

chisel.

How much of your own sensibilities are incorporated into your work

and how much of your work is faithful copies of originals?

A big

portion of my work is copies of originals. I get a kick out of seeing

something and then figuring out how to make it. My gun work will

sometimes be copies, but most of it is “inspired by”, as if I was working in a

particular maker's shop. Sometimes I will copy a gun at the customer’s

request which is always a bit more challenging than just working “in the

school”.

My silver

work currently is most often copies of mass produced period work. It’s

very important to a lot of my reenactor clients to be able to tie a piece to a

particular time and place for their persona. I’ve found that the more

I’ve expanded “my artistic vocabulary", as Wallace Gusler challenged me to

do, the more comfortable I am with doing my own thing rather than just copying

original work, and still have it look like it belongs in the period.

The animal designs you've been making are very compelling. Where

do the concepts for these come from?

The

animals on my trade silver for the most part are based and many times copied

from original 18th Century

work. I find them fascinating, with most being very “folky” and open to

different interpretations. It’s been speculated that many were engraved

by artists that had never seen the animals they were engraving, but were

working from other's sketches. Faithfully recreating them is an important

part of making believable and marketable reproductions of original silver

work. I have a few customers that I do my own original art work for.

Can you talk a little about exactly what a "peace medal"

is? Who made these originally and what was their purpose?

A peace

medal is a medal, usually worn around the neck that was a token of friendship

and peace that was gifted to the Native Americans first by the leaders of

Europe and later by the Presidents of the United States. It is the

American ones that I find interesting and reproduce. They were often

gifted at the signing of treaties and other interactions between the Native governments

and the United States governments. They were a means of recognizing the

Native leaders and were viewed as status symbols by those who received them.

Do any other contemporary makers influence your work?

I am

influenced by too many contemporary makers to list. There are many

different artists whose level of mastery that I aspire to reach. While I

will never live long enough to reach their level of work (and they keep getting

better!), it gives me goals to shoot for in my own work. As long as I

continue to see improvement in what I’m doing I’m pleased, but never too

pleased, as it sets a goal I can never quite reach.

What is your favorite type of work to do? Is there any particular

tool or material you feel absolutely comfortable and enjoy working with?

I really

enjoy anything that continues to challenge me. Woodwork and wood finishing are

probably what I feel most comfortable with as I’ve done it the longest, but I’m

really pleased with the improvements in my metal work and engraving as of late.

Do you apply the same approach to making all your work, or do you

need to change your thinking when making say a gun versus a gorget?

I

approach it all pretty much the same. I break gun building into many

smaller jobs so I don’t get overwhelmed. Sometimes when working on a gun

for a long time you can get frustrated by what seems like a lack of progress,

so viewing it as a series of smaller tasks helps to avoid this.

Can you tell us a little about the relationship between

Colonial-era America and silver?

Silver

was very important to Colonial America. Not only was it a symbol of

wealth it also allowed you to travel with your wealth, using utilitarian

objects like utensils, plates ,tea pots and candlesticks. Even if the object

was damaged you still had the value of the silver.

Trade

silver was also hugely important. The desire to obtain it was key in

commerce with the Native Americans. It was an important gift item and

item of trade. Huge quantities were traded to the Natives for furs, first

deer skins and later beaver skins in particular. It was a very important

form of currency.

One of the more interesting pieces you've made is the

"kissing otters". Where did the concept for this come from?

The

otters are based on an original Hudson Bay piece and are most likely 19th Century.

From studying original pieces, have you noticed any particular

evolution and differences in style from one time and piece to another?

There is

definably an evolution especially with the guns. You can trace the art

all the way back to the European masters with most of the art starting in the

pattern books of the royal French gunmakers then traveling to Germany then here

to the United States. Studying the details in the artwork of longrifles

is one of the best ways to trace where they were made and follow the makers and

their apprentices as they moved west.

Do you see any modern expressions of the designs, sensibilities,

imagery etc. that have their roots in the original work you've studied? Which

are subtle and which are obvious? Are any of them surprising?

I find that most of what I do and find interesting has it’s roots in the

old masters. Really nothing is new. If you search hard enough you will

find it’s been done before.

As a fellow Long Islander, I've always noticed how few makers

there are from there, as well as how Long Island's pre-20th century history is

often overlooked. Does the history, culture, and environment of

colonial-era Long Island have any influence on your work?

The town

I grew up in was settled very early (1639), and has a deep sense of history

which certainly was an influence on me. Because it is an affluent area,

many original homes have been preserved and restored, and a lot of the original

history has been researched and documented. Several of the town's original windmills are still in existence. The next town

over, Sag Harbor was an important whaling port and home of the first Customs

House. The ships captains' mansions are still there and restored, with

most featuring grand trim work and architectural detail done by ships'

carpenters of the period. My early construction career was spent

restoring many of these early structures. To do this requires a lot of

handwork. A large part of my business at the time was spent recreating

original architectural elements, which required 18th Century tools and techniques in order to look correct. It

also taught me to study things like tool marks in order to rediscover how

things are done.

What are you working on now?

I have a

couple of neat early rifles to do this summer; one is a Berks County and one is

a Christian Springs gun. I want to do a really folksy New England

fowler for myself if I can find the time. As for the silver work, I have

a couple of neat 18th century

silver boxes that I want to try and make. One is a copy of an English

nutmeg grater and several really cool tobacco boxes. There’s even an 18th Century horn and silver cucumber slicer in the works!

Interview by Eric Ewing.

Eric, Mitch; Enjoyed the interview, thank you. Jan, Art - thanks be to you also for bringing it.

ReplyDeletedave

Excellent interview and a real look into the work of a master!! Mitch is one of our most passionate artists and his heart comes through in all of his work. Wonderful gifts he gives us!! Thanks guys and Jan!!

ReplyDelete