May 1, 2013

The

blackpowder rifles that come out of Hershel House’s workshop hidden in the

Kentucky backwoods aren’t just exacting, made-from-scratch re-creations of true

frontier guns. The home-forged springs and screws, the hand-carved stocks, the

focus on function and reliability embody the history of America.

By

1780, the American frontier was changing. In Kentucky and Pennsylvania and

Virginia, in much of the old Ohio Territory and the big woods of Tennessee, the

baddest of the big game was largely gone. The eastern wolves that terrorized

the earliest settlements had nearly vanished, and so, too, the elk and bison.

Bear and mountain lion remained, and deer. But anywhere the ring of an ax was

heard, the report of the blackpowder rifle followed.

The

frontier had opened up. A man no longer needed a gun designed to hurl a

thumb-size hunk of lead into the nearest redcoat or hidebound predator or

painted Shawnee warrior. He needed a gun stingy with lead and easy to fix and

accurate enough to fill a bag with squirrels so he could feed all his kids who

busied themselves clearing trees for another field of corn. Once the scary

animals and natives were pushed from the verges of the American frontier, a man

no longer needed a big-bore thunderstick. He needed a rifle like the flintlock

Hershel House makes today, in the 21st-century hills of central Kentucky.

Wood, Iron, and Flame

Hershel

House is among the world’s most celebrated flintlock rifle makers. He

lives on a wooded knoll overlooking the broad Green River floodplain valley just

outside tiny Woodbury, Ky., where he was born and raised. His heavily timbered

property is littered with relics. Swages and coal forges crowd together under

shed roofs. Parts, pieces, and entire Model A’s are stored under soaring oaks.

His workshop is like a cluttered, narrow grotto, situated on the other side of

a dogtrot porch of a hand-hewn log cabin House has built over the last 15

years.

In

the mid 1970s, when the editors of the acclaimed Foxfire books

on Southern Appalachian heritage were looking for a rifle maker to profile,

they found their way to House and his tucked-away workshop. Since then, House

has built flintlocks for three Kentucky governors and for Fess Parker, who

played the title role in the old Davy Crockett TV series. He's

landed two National Endowment for the Arts grants to provide for gunsmith

apprenticeships, and restored the most credibly substantiated Davy

Crockett–owned rifle known to historians. That flintlock was "just a junk

pile" when he started, House says. It now hangs in the Tennessee State

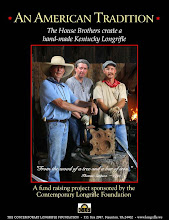

Museum. In 2009, House led a project—along with his brothers John and Frank,

celebrated craftsmen in their own right—to build a special-edition Kentucky

long rifle as a fund-raiser for the Contemporary Longrifle Foundation. Every

piece of metal was forged by hand. It raised $140,000.

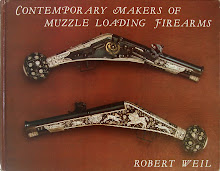

House

does turn out embellished guns, such as this double patch box southern mountain

rifle.

All

told, House has built some 300 pistols, shotguns, Indian trade guns, and both

flintlock and percussion rifles. And built does not mean assembled

from kits. In all cases, House forges the main components of the guns,

and in many cases, he has forged every single piece of metal down to the

springs. He's made highly embellished firearms that sold for better than $10,000,

although his last three rifles were simpler affairs that went for between four

and six grand. "I reckon I've got a name now," he says, grinning.

"Guys that bought those guns for $300 back in the '70s wish they'd held on

to 'em." In fact, House-made guns are so sought-after and valuable that he

himself owns but one.

Watching

House work helps tease apart the tangled genealogy of the American frontier

long rifle. The relationship between Kentucky rifles, Pennsylvania rifles,

mountain rifles, squirrel rifles, and Tennessee rifles—all somewhat loosely

applied terms—comes into finer focus. "They were all based on the big

German Jaegers," House explains, referring to the rifled-barrel flintlocks

brought by European immigrants that showed up in Pennsylvania sometime around

1709. Over the next hundred years the guns evolved into the fully stocked,

octagonal-barreled rifled muzzleloaders with the crescent buttplates that would

establish the reputation of both famous frontiersmen and a young nation itself.

Broadly speaking, the term Kentucky rifle refers to big-bore

guns built in the highly embellished style based in the Lancaster, Pa., region.

The Kentucky reference grew from a wildly popular 1826 ballad that celebrated

the feats of Kentucky hunters at the 1815 Battle of New Orleans. Later, a

shorter, heavier, larger-bore version—the Hawken rifle—showed up on the Western

plains.

House

makes major metal components of each gun -- in some cases, every piece.

But

the rifle for which House is most recognized is a firearm more restrained and

straightforward than many carved and engraved Kentucky rifles. It’s a

.32-caliber squirrel rifle—a smaller, slender, subtler subspecies. Plainly

outfitted with iron mountings instead of polished brass, it was a gun common to

the frontiers of Virginia and the Carolinas from 1790 to about 1835. It is

simple and elegant and frightfully deadly, and seems as fitted to House and his

own life story as a hand-carved stock to a hand-forged patch box.

“You can see it here,” House says, bending

over a rifle that appears to be perhaps half completed. This current project—he

rarely works on more than one gun at a time—is a squirrel rifle for a customer

from California who has taken a number of House’s gunmaking classes. (House

leads multiday gun-building and knife-forging seminars from his Kentucky shop

several times a year; for details, contact him at 270-526-3493.) “A squirrel

rifle was sort of a fork in the road for the old blackpowder gunsmiths.” Once

the basic elements were in place—locks, stock, and barrel—gunmakers could

embellish the gun with elaborate carvings, engraved patch boxes, and highly

figured buttplates and other metalwork. Or they could produce a gun far more

suited to the evolving frontier edge.

By

the latter decades of the 18th century, two factors drove the development of

the squirrel rifle. First, the ornamentation of the earlier rifles was

considered a drawback for frontiersmen who relied on the guns to feed large

families. The engraved brass and silver mountings were expensive, and they

glinted in the woods, scaring game. Squirrel rifles instead used iron fittings

easily forged and fixed in the backcountry. The patch box itself was something

you could do without, and save a few cents. A channel was carved into the stock

for storing tallow for patch lubrication.

“On

an earlier gun,” House explains, pointing to the gunstock just behind the lock,

“they would carve a raised, ornamental panel called a beavertail right here.

But you get into these squirrel rifles and those penny-pinching mountain folk

didn’t want to put on airs with a fancy rifle. Some didn’t even have

buttplates. They wanted the gun to be good and deadly. And if they didn’t have

to have it, they didn’t want it.”

House

has blue eyes set in an angular face like a hatchet, and a thick Beatle-like

mop of brown hair despite the fact that he turned 70 years old last July 4. As

he works a fine rasp between the lock panel and the stock’s wrist, sawdust

falling like fine snow, House talks. After the American Revolution, “powder was

hard to get and expensive, and lead was tougher to come by.” By making smaller

guns, you used less lead and powder. “A .32-caliber squirrel gun would still

kill a man if you hit him just right. And it would definitely kill a deer or a

wild hog. But times were awful hard. I’ve read of guys that would shoot a

squirrel in a tree then take their tomahawks and dig the bullet out and chew it

back round to use it again. That’s how valuable the lead was.”

The

squirrel rifle enabled hunters to forage the quickly civilizing edge of the

western frontier, a place shifting rapidly from utter wilderness to a kind of

prototypical suburbia. And that’s why American frontiersmen became such

noteworthy marksmen. Game was getting scarce; lead was expensive. Every time

you pulled the trigger, it had to mean something.

Which

is why a rifle like the one that House makes will tell you the story of

America.

Afield With the Smith

Varmint!

House in the squirrel woods near his workshop.

You

can tell when House is hunting because he will have a powder horn and bullet

pouch around his neck and his squirrel rifle in the crook of his arm.

Otherwise, he might look as though he's simply on the way to the forge or the

post office. There's no fuss about it. Hunting is seamlessly integrated into

the warp and weave of House's life—off for an hour or two after chores, before

the sun goes down, him and his dogs. He wears jeans and running shoes, a

green-and-black plaid jacket, a grimy Red Man ball cap—what he's been wearing

all day in the shop. He whistles up Liddy and Fred, and steps off the cabin

porch, and he's hunting. "Come on, let's go, find us some varmints,"

he sings out as the dogs prance and pee. It's a term House tosses about frequently—varmints—and

I never quite figure out if it refers to squirrels, anything but squirrels, or

everything including squirrels. Whatever shows up, though, opossum or raccoon

or rabbit or squirrel, is likely to get shot, and just as likely to wind up in

a black iron stewpot.

Now

Liddy and Fred streak after a rabbit jumped from the crown of a blown-down oak.

They lose the rabbit before they can put on a good race, but House is

unperturbed. He moves through the woods with a casual pace, eyes on the branches

overhead, letting the dogs do their work. I follow behind, watching House cap

out on winter-bare ridgetops, with soaring views of the corrugated, folded

Kentucky countryside unfurling across the Green River. At one point he is

silhouetted against the sky, framed between the squat outlines of his home and

shop, with open fields butting up against towering oaks. It’s a scene right out

of the flintlock days, when a cabin and a rifle were all that kept the

wilderness at bay.

House

felt this pull of old frontier life as early as his own childhood. Growing up,

he made his own coonskin caps and hunted long and hard and often alone. “I

didn’t know anybody else cared about the old stuff,” he says. In the mid 1950s

he found an old half-stocked squirrel rifle in the barn of a family friend. He

fixed it up and started laying the squirrels out with round lead balls. Within

a few years later he’d saved up enough money to order a barrel and a few pieces

of hardware from Dixie Gun Works. Everything else he “beat out” on a forge. It

was an experience that introduced him to a world he didn’t know existed. “When

I found that Dixie Gun Works catalog,” he says, “I thought, Man, maybe I’m not

the only crazy person out there.”

After

a brief stint in the U.S. Marines, House returned home to Woodbury and set up

shop as a full-time blackpowder rifle maker. At first, it was hardly a

lucrative business. It would be a long time before blackpowder hunting would

reach the mainstream, and even today, hunting with a rock-lock is a curiosity

at best. One day a few years back House was squirrel hunting along the ridge

behind his house and ran into a deer hunter who hollered out, “What are you

doing with that stupid rifle? You can’t kill nothing with that old thing!”

House

snapped back. “What do you think happened to the original deer herd in these

parts, boy?” he said, patting his flintlock. “Guns like this old thing—that’s

what!”

After

the hunt, we head to House’s kitchen, where he piles plates with white beans

and ham hocks and fried hoecakes made from cornmeal he ground himself. Shelves

of a hutch cabinet are warped with the weight of a hodgepodge of put-up

vegetables and deer meat, cans of rifle powder, and old blue-ware china. There

are stacks of books on colonial history, biographies of Daniel Boone, and

scholarly tomes on bayonets and antique engines.

This

allure of the ways of old permeates every aspect of House’s craft, and his

approach to gunmaking has evolved into a distinguishable style whose warm, soft

lines now define what is known as the Woodbury School. He “browns” a gun’s

metal parts by boiling them in a bleach-and-water solution that pepper-rusts

the metals. “It gives them that lightly pitted look that breaks up the glare,”

he explains, “and softens the corners and hammer marks. It makes them look like

an old rifle that has been taken care of but still used good and hard.” He

prepares gunstock stains from an old recipe—horseshoe nails and iron filings

dissolved in nitric acid—and uses heat to drive the mixture deep into the wood.

When

he first started making these guns, “I caught hell for it,” he recalls. “People

said I was building fakery guns, that a new gun ought to look like a new gun.

But I kinda like it, and it turned out that a whole bunch of other folks kind

of liked it, too. So I’m glad I never listened to those folks.”

Given

his love of blacksmithing and knifemaking and old engines and stone-ground

meal—even the Model A’s that he drives all over Kentucky’s Butler County—it

might be easy to think that Hershel House is a man living in the wrong era. But

his realistic grasp of those bygone days, and their difficulties, turns aside

such romanticisms.

“I

get that a bunch,” he says with a grin, and shakes his head. “Everybody says I

ought to have been born 200 years ago. But it was too hard a time back then.

Little kids dying of pneumonia. Indian wars. Maybe I would have survived more

so than a lot because I have a familiarization with the long rifle. But it’s much

more fun to play that role now than it would have been to live it.”

Making Frontier Meat

In

the morning, House sends me out on my own. Fog hangs low in the valley. I have

his squirrel rifle in my hand, his hand-carved powder horn, powder charger, pan

primer, and ball loader on a leather thong around my neck. The woods at dawn

are crawling with squirrels. Within 45 minutes I miss four. I miss squirrels

stretched out on the trunk of a beech tree and balled up in the crook of a

poplar and feeding in the twiggy boughs of a pine. I miss them from 60 feet to

150. Try as I might, that flash in the pan, the smoke and sizzle-puff and the

brief hesitation between the pull of the trigger and the blast of the powder is

just disconcerting enough that my aim can’t quite hold.

I

reload carefully. Pull out the wooden powder-horn plug with my teeth. Fill the

powder charger that holds the correct load. Replace the horn plug. Pour the

powder down the barrel. Place the bullet loader with its patched balls over the

muzzle. Ram a bullet home. Replace the ramrod. Put the gun on half cock. Pour

powder from the flash powder horn into the concave dip of the flash pan. Set

the flash guard against the powder. Ready. As I am shaky with the process and

trying to hide from squirrels, this takes approximately three minutes. One

thing’s for sure—I’d have been picked off by a redcoat or a warring native long

ago.

I

have done this since I was a child, slipped along slowly below the crest of a

hill, eyes open, heart pounding at every little twitch of a twig or limb. I’ve

killed squirrels with shotguns, with rifles from boats in swamps, killed them

with Cajuns, killed them over squirrel dogs and over the gunwale of a canoe.

But I’ve never tried to kill one this way, the way that sustained America, with

a flintlock rifle in hand.

Now

another squirrel is headed my way, and I bury my left shoulder into the pale

bark of a beech. Hugging the tree, I peek around. He’s headed for a pine and I

know why. I can see the nest. He stops and hesitates, like a deer looking over

its shoulder, and I touch the double-set hair trigger.

This

time, after the flash, the squirrel tumbles through the smoke, hits the leaves,

and lies still as a stone. I stifle a whoop of glee but can’t help but

fist-pump in a very un-pioneer-like fashion.

In

the end, one squirrel out of five opportunities won’t make me a Kentucky

rifleman. But it will make me what Kentucky riflemen have sought with a

squirrel rifle since the days when America was just a dream. It’ll make me a

fine supper.

Copy and photos from Field and Stream Magazine here.

Copy and photos from Field and Stream Magazine here.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.