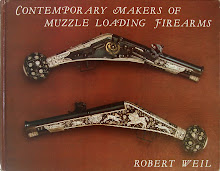

A pair of rare early flintlock holster pistols [Fig.1], the

subject of this article, were recently returned to Dunster Castle (National

Trust) after an absence of 40 years. They had been part of the famous Dunster

Armoury which was established in the late 1670s by Colonel Francis Luttrell

(1659-1690) when he formed his own militia regiment. The Armoury at Dunster

remained intact until the early 1970s, just prior to its acquisition by the

National Trust, when the majority of the guns, mainly the 17th century muskets,

were sold to Dr Robert Rabett, a private collector, by Walter Luttrell

(1919-2007). The subject pistols then remained in Dr Rabett’s collection until

his death in 2011 when the Trust bought them at auction (Bonhams, London; Fine

Antique Arms & Armour: The Dr Robert Rabett Collection).

The pistols date to the period 1665-1675 and are almost

certainly among those mentioned in the Castle Inventory of 1705. They were

probably part of the military equipment acquired by Colonel Francis Luttrell

(1659-1690) when he formed an Armoury and militia regiment at the Castle in the

late 1670s, and may even have been his own pistols.English military pistols

from this period are extremely scarce and only a very small number are known to

exist. Although on first appearance they may seem plain and devoid of any

obvious decoration, there are some subtle decorative features that will be

pointed out in the description that follows.

The pistols are large, 53cm (21inches) in length, and are

designed to be carried in saddle mounted holsters. They do not follow the very

graceful lines that are seen in civilian holster pistols of the period, but in

comparison are rather heavy and solid in appearance, especially around the lock

and butt, which is more typical of military pistols

The iron barrels are 36.2cm (14.inches) in length, and of 14mm calibre (28 bore). They are formed in four stages; octagonal at the breech, becoming sixteen sided, then round for a short length, reducing to a smaller diameter section at the muzzle. Each stage is separated, firstly by small concave indentations and then by moulded rings, which has the effect of tapering the barrel in a uniform way and being very pleasing to the eye [Fig.2]. The barrel is held to the stock by two transverse pins passing through the fore-stock and a long screw with a large dome head that is inserted upwards from the trigger guard finial into the barrel tang.

The top breech flat of each barrel is deeply stamped with a crowned S, which is large and distinctive [Fig.3]. This mark appears to be unrecorded, but recently published information suggests it could be the mark of gunsmith Walter Solcombe, recorded as working in Dunster between the period c1657 to 1676 (Somerset Record Office).

The walnut full stocks, whilst quite chunky, fit the hand well. The pommel of each butt is strengthened with an iron band, a feature first seen on English military pistols of an earlier period [Fig.4]. The rear top edge of the butt is flattened and extends from behind the barrel tang apron to the pommel band. A long and shaped raised apron has been carved behind the barrel tang and some profile carving can be seen around the ramrod channel and to the rear of the lock recess. The left side of the stock, opposite the lock, mimics the flattened lockplate and is carved in profile around the edge. A small but well executed touch is the decorative chiselling on the top edge of this, near to the breech [Fig.5].

The pistols have plain iron trigger guards with spear-shaped finials and long rear tangs, which are nailed on [Fig.6]. Each have a single iron ramrod pipe, but no rear pipe and neither pistol has a muzzle band. The pistols have wooden ramrods without metal tips, with one ramrod terminating in an iron worm (the other ramrod has lost its tip) [Fig.7]. The curved and rather broad triggers are suspended from a pin inserted just above the rear of each lock [Fig.8]. The Type 2 English Locks are of classic form, with flat plates and flat, full breasted cocks. The plates have bevelled edges, the tails of which terminate in long pointed finials. Behind each cock is a sturdy dog-catch that holds it in a safety position between half and full cock. It is automatically released when the pistol is brought to full cock. The frizzens have pointed tops with facetted backs. The pans are also facetted, being forged separately from the plates, and each is held in place by a tapered rivet. Whilst being of a fairly plain and solid execution, the work has small touches of filed decoration, reflecting the individuality of the gunmakers art that dominated even military firearms of the day. This decoration can be seen on the top edge of the plate behind the pan; on the comb of the cock; and on the frizzen and the frizzen spring [Fig.9].

Internally, the locks use a horizontally acting sear, a characteristic of the English lock, to engage with projections on the tumbler to provide half and full cock [Fig.10a & b]. Again, the work is robust and functional. The locks are held to the stocks by three side-nails. No markings have been found on either lock.

The small decorative features of these pistols are typical of the period before the introduction of the first “Pattern” or regulation issue military pistols, which were first introduced by the Ordnance during the 1680s. Although perhaps insignificant, these small features, the whims and fancies of an individual gunmaker, were not part of the new regulated Ordnance firearms that followed this period. They therefore mark an important changing point in the design and production of British military pistols and consequently were the last of their type.

Since well before the Civil Wars (1642-1651) English military pistols had typically been long and cumbersome weapons. In 1630 the Council of War decreed that pistols should be 26 inches in length (66cm), with an 18 inch barrel (46cm) and of 24 bore (14mm). By 1639, Ordnance officers concluded from tests, that a 16 inch barrel was as accurate as one of 18 or 20 inches (“British Military Firearms”, H.L.Blackmore, London 1962; page 24). By the time of the Civil Wars in 1642, the average pistol barrel length had reduced slightly and was now 14–16 inches (35.5– 40.5cm), making the whole pistol around 20–22 inches (51.5–56cm) in length. Although slightly reduced, this size still made the pistols unwieldy and rather unpopular (Based on a survey of the 44 Civil War pistols of English origin in the Littlecote collection – see “Littlecote – The English Civil War Armoury”, Thom Richardson & Graeme Rimer, Leeds 2012). Overall lengths of British military pistols averaged around 20 inches (51.5cm), until the reign of Queen Anne in 1703.

By 1685 those British military firearms using the old English Lock mechanism were being removed and replaced by muskets and pistols with the simpler “French lock”. These were as efficient, had fewer parts and were easier and cheaper to produce. Unlike the English Lock, the new French locks were very plain, with each one copying a “Pattern” designated by the Ordnance and so they were almost identical, despite being made by different contractors. The locks did not include the little individual touches and whims of the gunmaker who made them, as the locks of the previous generation had done. The stocks and mounts of Ordnance pattern pistols were equally plain and very functional and again devoid of any of the gunmakers personal touches. All were of exactly the same form, with only the essential markings of the maker and of Government ownership. “Double Springes French Locks with Kings Cypher engraven” were the order of the day, according to Ordnance records of 1685 (“British Military Firearms”, H.L.Blackmore, London 1962, page 36). In the process of this great change to British military firearms, much of the old equipment from an earlier period was sold, or discarded and lost forever. Dunster Castle only just survived being destroyed in the English Civil Wars of 1642-1651. In 1670 Dunster had a new owner, the young Francis Luttrell, aged 11, who inherited Dunster after the death of his father and older brother. Following his marriage in 1680, Francis set about dramatically changing the former Castle into a stately home befitting a new era. He joined the Somerset Militia, forming and equipping a troop of his own and furnished an Armoury with at least 44 flintlock muskets and other arms, including at least 2 pairs of flintlock pistols. In 1685, Luttrell’s regiment joined with others of the Somerset Militia to help repel the rebellious forces of the Duke of Monmouth, who were attempting to take the Crown. In 1688, with the onset of the ‘Glorious Revolution’ and the overthrow of James II, Luttrell joined the forces of William, Prince of Orange, who had landed at Torbay. Luttrell managed to raise a regiment of foot in only three days, partly due to his organisational abilities and partly because of the substantial Armoury at Dunster.

While it is tempting to suggest that the subject pistols were intended for Francis Luttrell’s own use, the evidence to back this remains a supposition. The pistols are of the right date; they could have been made by Walter Solcombe of Dunster, who died in 1676; and they are almost certainly those mentioned in a Castle Inventory, shown below, which was taken 300 years ago.

In 1705 a complete inventory of the Castle was taken, which not only recorded “43 musquetts and collars of bandoleers” (the remains of the old Armoury), but also “2 paires of pistols”. In 1741 another inventory was taken, which recorded, “42 Musketts & a parcel of old Bandoleers (the Musketts being very old & Useless)” and “One Brace of Long Pistolls”. In a further Inventory, taken in 1910, the remains of the old Armoury are recorded as, “39 Old Flint Guns, much worm eaten and 3 old Flint and Steel Pistols”. This would seem persuasive evidence to suggest that they are indeed the pistols mentioned in the above Inventories.

*For an explanation of the English Lock types see – Godwin,

Cooper and Spencer, “The Origins and Development of the English Flintlock”,

London Park Lane Arms Fair catalogue, 2002.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the staff at Dunster Castle, in

particular David Moore, for their

help.

Copy and photo credit: Brian Godwin U.K.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.